1993

8 Type C photographic images

107 x 107cm

edition of 6

8 Type C photographic images

107 x 107cm

edition of 6

Exhibitions

1993 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by Peter Gill, Muswellbrook Regional Art Gallery

1993 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by Audrey Banfield, Albury Regional Art Gallery

1993 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by William Mora, William Mora Galleries Melbourne

1994 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by Martyn Jolly, Canberra School of Art

1993 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by Peter Gill, Muswellbrook Regional Art Gallery

1993 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by Audrey Banfield, Albury Regional Art Gallery

1993 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by William Mora, William Mora Galleries Melbourne

1994 Deciphering the Unseen w/ Ruth Thompson, curated by Martyn Jolly, Canberra School of Art

No Place Like Home: some notes on Deciphering The Unseen

essay by Dr Martin Thomas

essay by Dr Martin Thomas

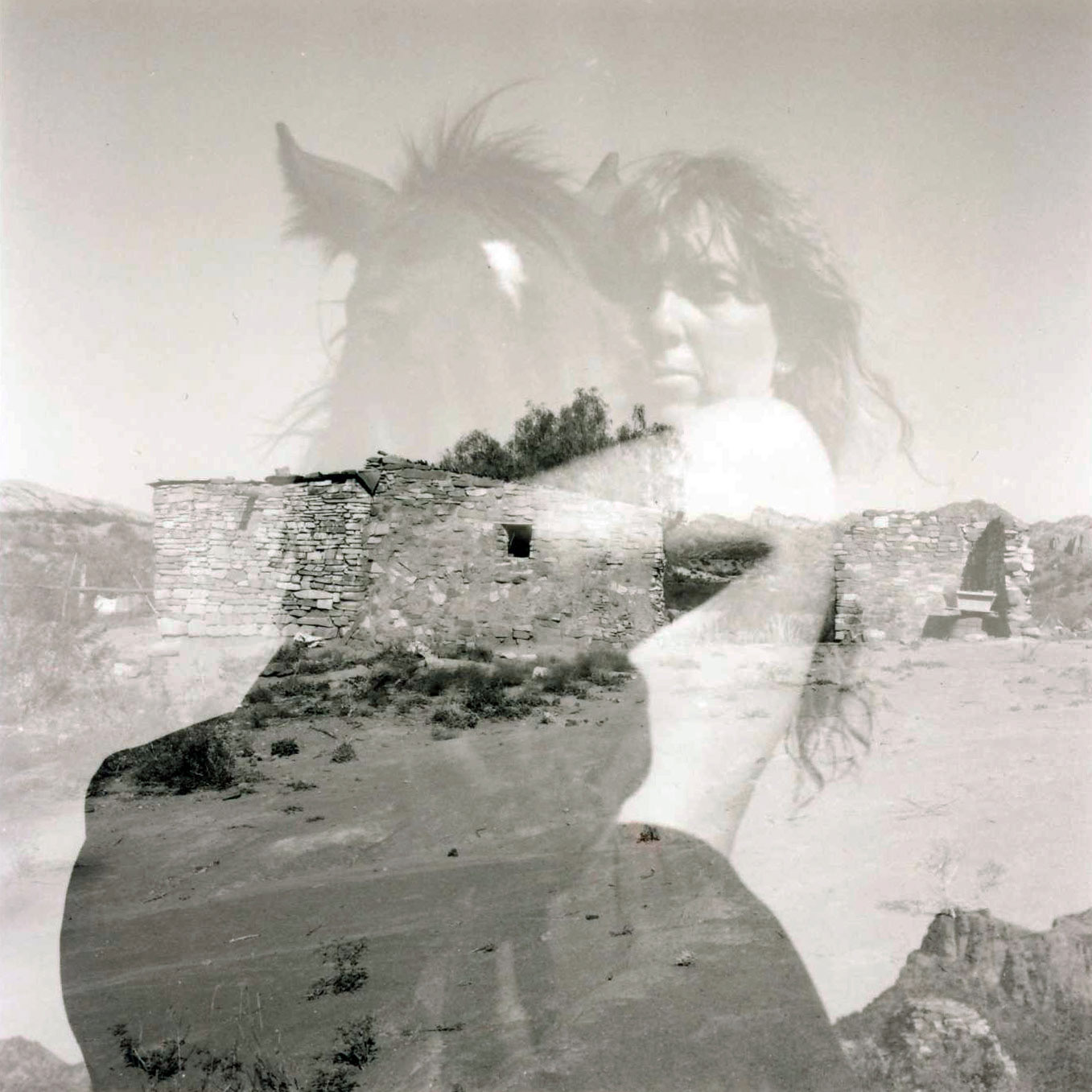

When I first looked at these surreal experiments in self portraiture by Ruth Thompson and Julie Williams, with their evocations of ghosted bodies – flesh superimposed by stone and bone – I was reminded of Leah King-Smith’s exhibition of photo-compositions that toured Australia in 1992. Of course there are profound differences: the translucent figures haunting King-Smith’s gently coloured landscapes are Aboriginal Australians ‘released’ from archival collections of nineteenth century photographs and symbolically returned to stolen ground, while Thompson and Williams are white Australians whose image-making is based on travel – on departing from a point of origin.

There are, however, certain commonalities that might explain the resonance between these exhibitions. Both allude to the fragmentary manner in which photography allows one to construct a personal history. And they both locate transparent figures within landscapes to problematise assumptions about habitation. Thompson and Williams were born into rural Australian towns departing as “misfits” in their late teens. Read on the most obvious level of psychobiography, their photographs articulate a sense of displacement: that the communities they rejected offer no community; that they have no place like home.

I would argue that a political issue haunts this personal crisis. The corollary of the dilemma articulated by Leah King-Smith is that the dispossessors or their descendants are spiritually homeless. The signs of this are common across much of Australia, not least in the often dismal state of inter-racial relations. Lacking a mythology that connects them with the land – and having so far failed to negotiate a treaty with its original owners – white Australians will attempt to compensate for their ungroundedness. The frame of a landscape painting, like the fence that encloses a field, becomes a declaration of ownership. For similar reasons, a farmhouse will often display an aerial photograph of the property on which it is sited.

The shooting of the eight images that comprise Deciphering the Unseen commenced in 1992, a year that problematised notions of possession in an auspicious manner. In South America, where the photographs were taken, the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival was being mourned and celebrated. In Australia, the High Court handed down a landmark judgment that acknowledged, for the first time since European invasion, the existence of “native title”. The decision has given legal sanction to Aboriginal people who are attempting to reclaim stolen territory. As much as anything, it marks a symbolic victory for Aboriginal Australia. The doctrine of terra nullius (the British misconception that prior to invasion Australia was an uninhabited continent) is now officially discarded. This judgement is also symbolic to landed Australia – a reminder that possession is a flimsy notion.

The connection between a rendering of ‘the real’ and modes of possession is a well developed theme in art criticism. Similarly, the desire to disrupt the monostatic assumption that a photograph ‘captures’ a slice of real time has motivated artistic innovation for more than a century. The devices for doing this are numerous. Some photographers use montage, while others devise and photograph scenarios that are deliberately fantastic. Another technique, the simple process of double exposure, has been used in all but one of the images in Deciphering the Unseen. This is achieved if the winding mechanism on a camera is arrested, allowing the photographer to shoot two images on the same piece of film. Most camera users have had experience of this, perhaps where the film fails to wind on accidentally. Usually they will discard the blurred or ghosted images as “mistakes”.

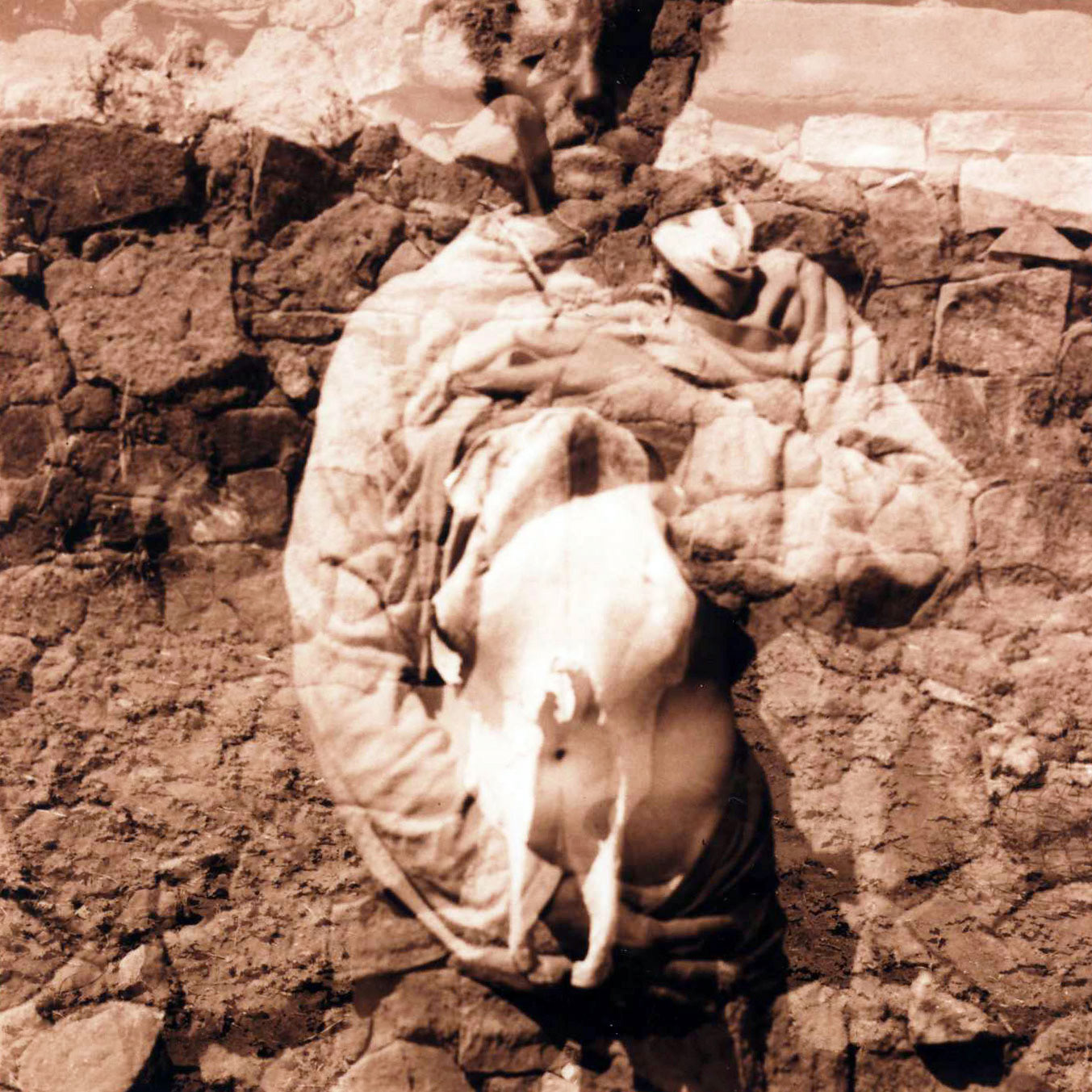

The photographs here are anything but mistakes. Those displayed have been selected from more than one thousand double exposures. They were taken on black and white film and printed on colour paper. The use of specific filters in the printing process has provided each image with its distinct tonality, and suggests a painterly quality.

The sense of the painterly – the manner in which the photographers have, through their multiple exposures, applied layers of image to the film emulsion – disrupts the notion of a unified temporal field and crams a multiplicity of times, places, memories into the pictorial surface. It also highlights a sense of the symbolic. A bone in the context of these pictures is no longer just a bone, and object lying in a paddock. The weird juxtapositions, the sense of unreality, seem to draw from the experience of the dreamer. The tendency of dreams to transform objects in to symbols is what intrigues and puzzles the awoken consciousness. Thompson and Williams, in adopting a dreaming language, highlight a theme emphasised by many dream experiences: the concurrence of personal and collective memory.

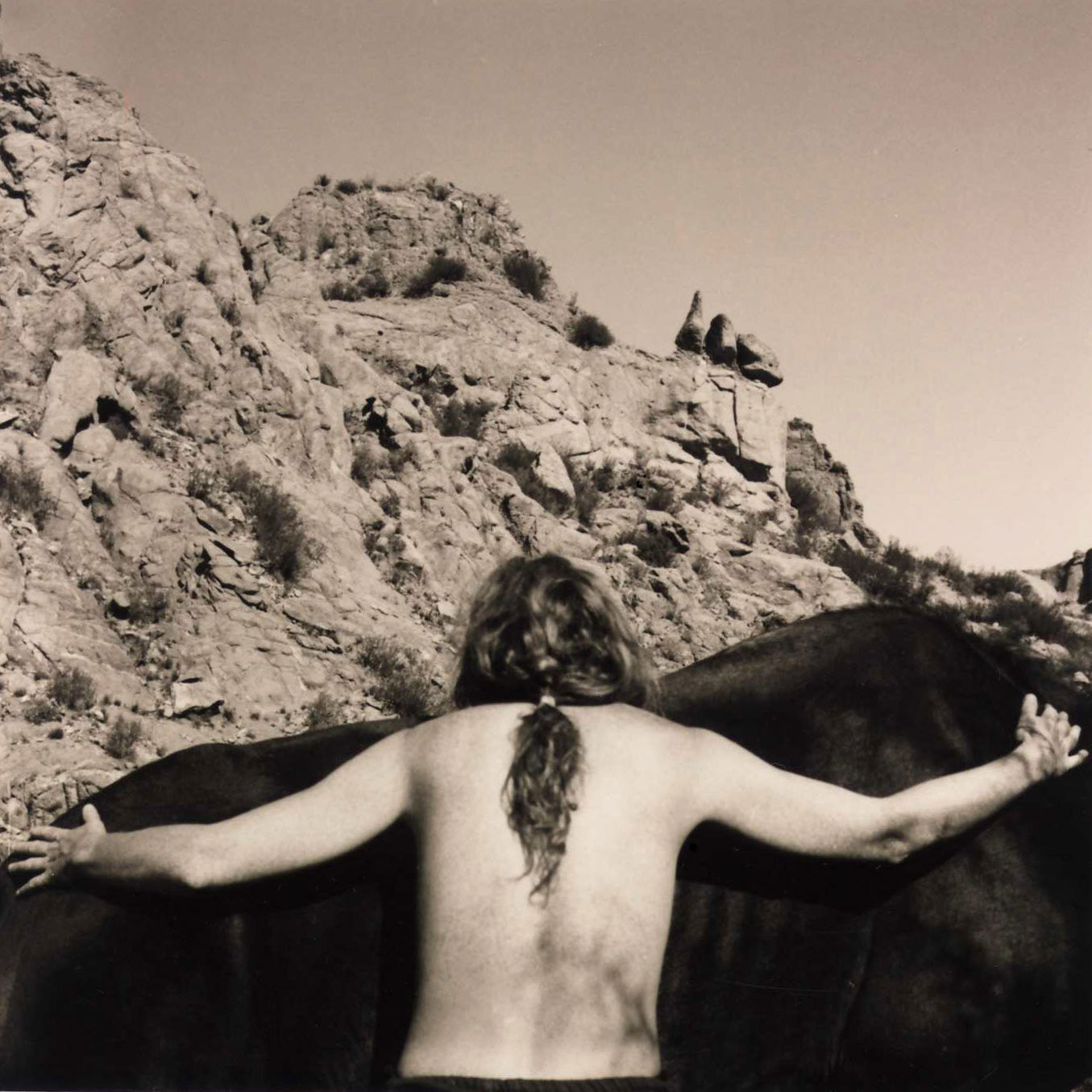

This discovery of a conjunction between individual and communal experience was one of the factors that brought the photographers together. During the early days of their friendship, Julie and Ruth compared childhood photographs. Playtime activities for both girls had involved games concerning horses. A photo shot in Muswellbrook, 1965, shows Julie in cowgirl outfit pointing toy six-shooters at the camera. Ruth was captured in the same year pushing a toy horse in a pram. In another of her childhood snaps she holds a leather harness while the horse it belongs to roams unrestrained in the distance. A curious detail in this image is the pair of clasped, masculine hands that seem amputated by the edge of the frame. Perhaps a visual genealogy of Deciphering the Unseen can be detected in these extracts from the family albums. To what extent is Ruth’s self-portrait in Number 3 a re-processing of that childhood scene? She wears a stockman’s hat, carries a harness and stands beneath a gum tree, which, strangely enough, was growing in the Argentine mountains. And what of the substitution of arms for bones in Numbers 1 and 2? Could a link be drawn between the haunting, skeletal symbols and the severed limbs of the male observer?

The dominance of horses in the childhood photographs points to a common fantasy that the photographers chose to work with and explore by embarking on a horseback journey in Argentina. I don’t intend to say much about the journey itself, except to observe that the venture was not the grand expedition they had envisaged. A dubious trader in San Raphael (western Argentina) sold them two ailing horses and an unfortunate mule that was later estimated to be one hundred years old. The horses collapsed after 50km and thus the bold plan to travel the Andes came to a pre-emptive conclusion.

Disappointing as this must have been, the fact the their trip finally involved a more sustained habitation, rather than a transition through many places, had a profound impact on the exhibition. Located for six months in the foothills of the Andes (in the province of Mendoza), Williams and Thompson found the opportunity to work at their image-making on an almost daily basis. Living with a young stock woman in a stone dwelling, they commenced the process of experimentation that gave birth to the images that we see.

I write birth quite pointedly in this context. The images have, quite literally, emerged from the exposed torsos of the subjects. Look for the signs of femininity which crowd the photographs. Consider the central position of the window that coincides with Julie’s arm in Number 4 and the view of Ruth’s navel, framed by the skull in Number 6. These apertures suggest umbilical connections, emphasising the the persistence of life among all those bones – the signs of death.

It would be reductive to isolate a dominant theme in these multi-layered photographs. Each viewer, I hope, will come to a unique and individual conclusion. But the impression that affects me most strongly is the sense of floating or flying that imbues so many of these dreamscapes – emphasised most strongly in Numbers 1 and 2 where the jaw bones have, in a sense, become wings and where the subjects seem ready to ascend above or perhaps melt into the stone wall that positions them. That is where these photographs reveal a certain timeliness. They raise a question about the spirit of place – about how we can inhabit a location most fully. If they offer an answer, it is surely in the suggestions of flight, movement, transcendence: the assertion that to inhabit is not to possess, but to endow with the imagination.

© 1993 Dr Martin Thomas

Dr Martin Thomas, Historian, Australian National University