Untitled #1

Untitled #2

Untitled #3

Untitled #4

Untitled #5

Untitled #6

Untitled #7

Untitled #8

Untitled #9

Untitled #10

Untitled #11

Untitled #12

Untitled #13

Untitled #14

Untitled #15

Untitled #16

Untitled #17

Untitled #18

Untitled #19

Untitled #20

Untitled #21

Untitled #22

Untitled #23

Untitled #24

Untitled #25

Untitled #26

Untitled #27

Untitled #28

Untitled #29

Untitled #30

Untitled #31

Untitled #32

32 photographic images

pure pigment prints on photo rag

75 x 50cm edition of 5 + AP

50 X 30cm edition of 3

pure pigment prints on photo rag

75 x 50cm edition of 5 + AP

50 X 30cm edition of 3

Exhibitions

2012 Water Magicians curated by Sandy Edwards, Syndicate at Danks, Waterloo

2011 When First I Knew This Place curated by Caroline Edwards, Regional Art Space, Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo

2012 Water Magicians curated by Sandy Edwards, Syndicate at Danks, Waterloo

2011 When First I Knew This Place curated by Caroline Edwards, Regional Art Space, Western Plains Cultural Centre, Dubbo

Catalogue Essay

by Dr Naomi Parry

by Dr Naomi Parry

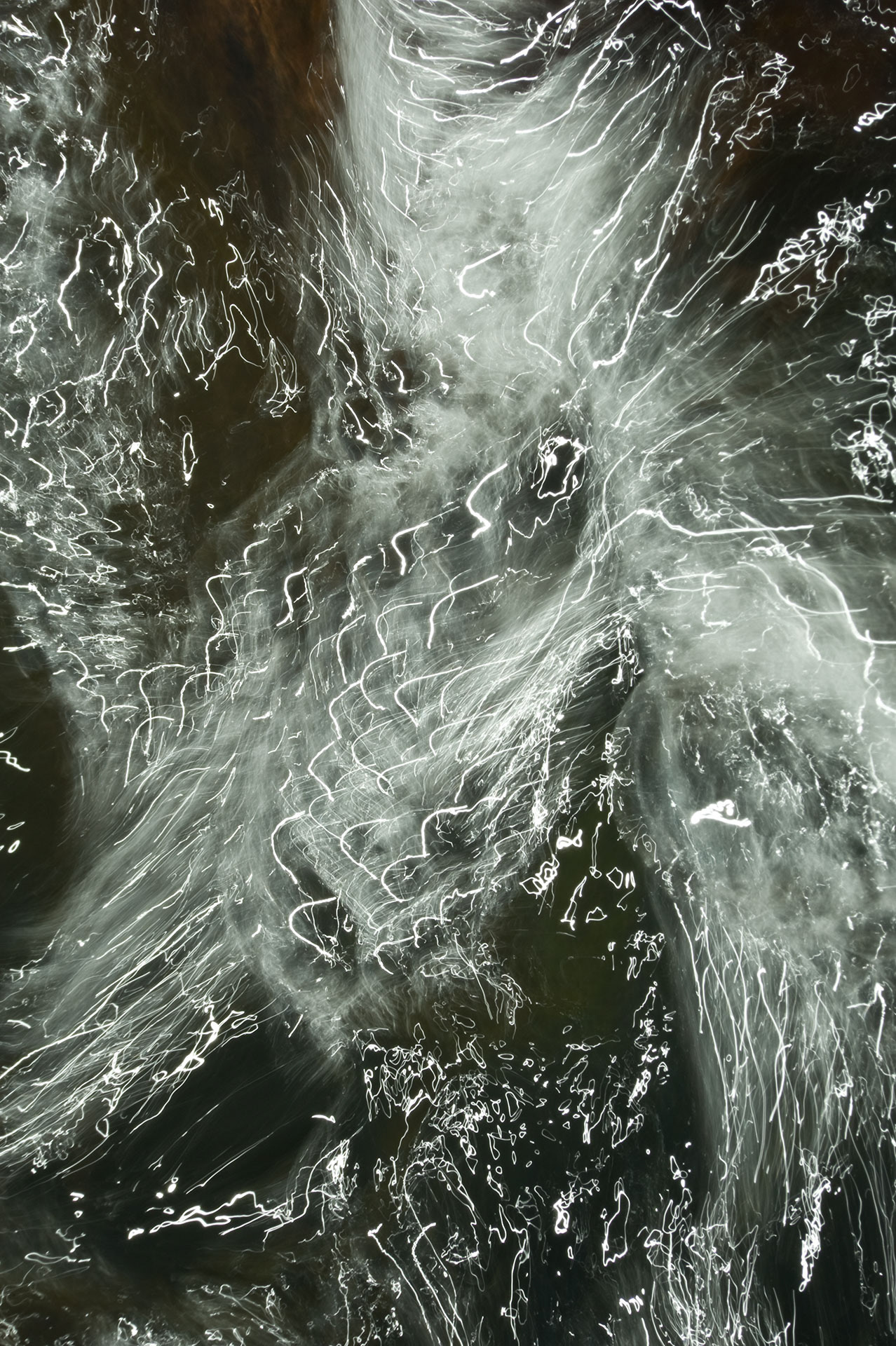

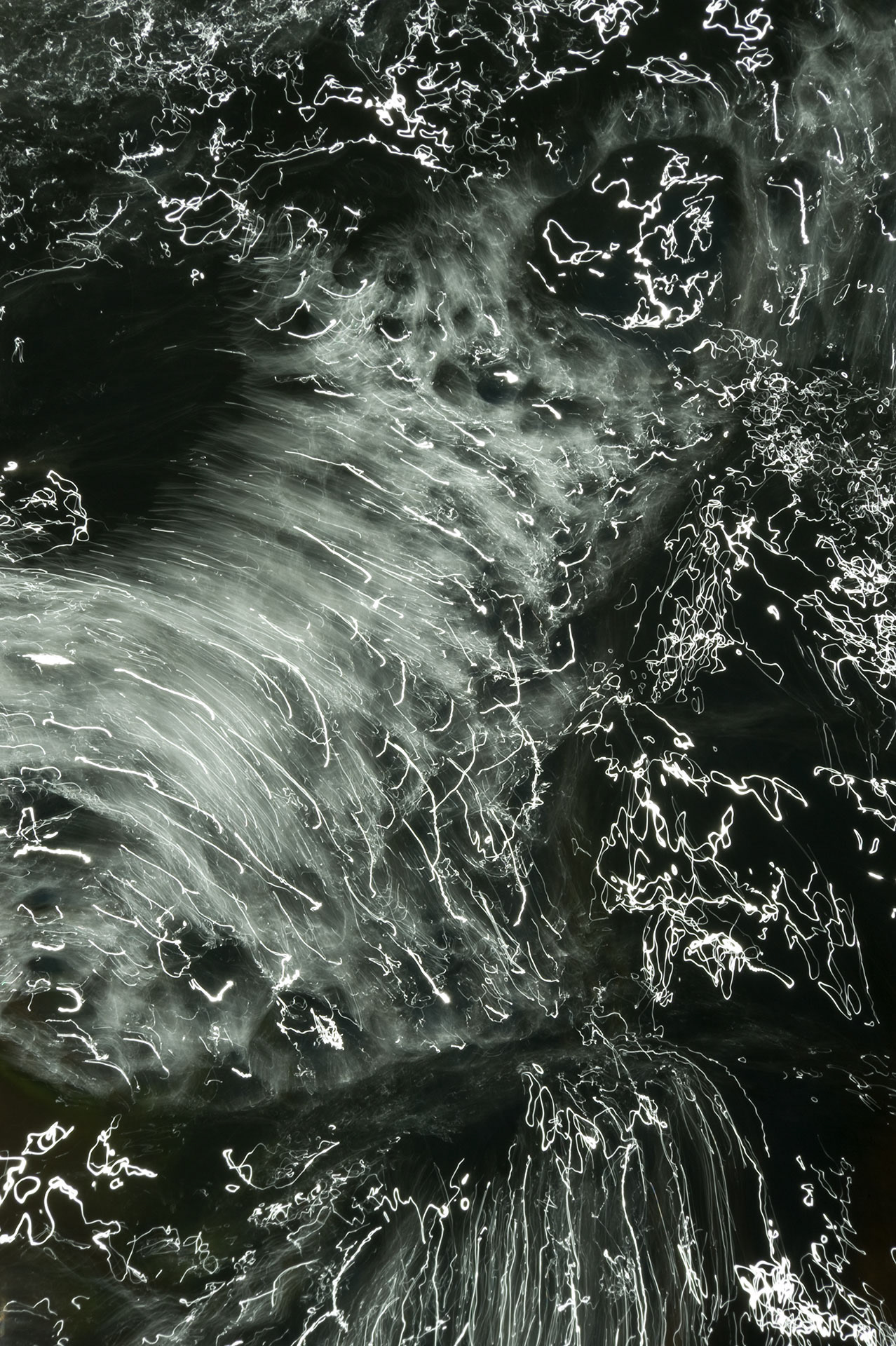

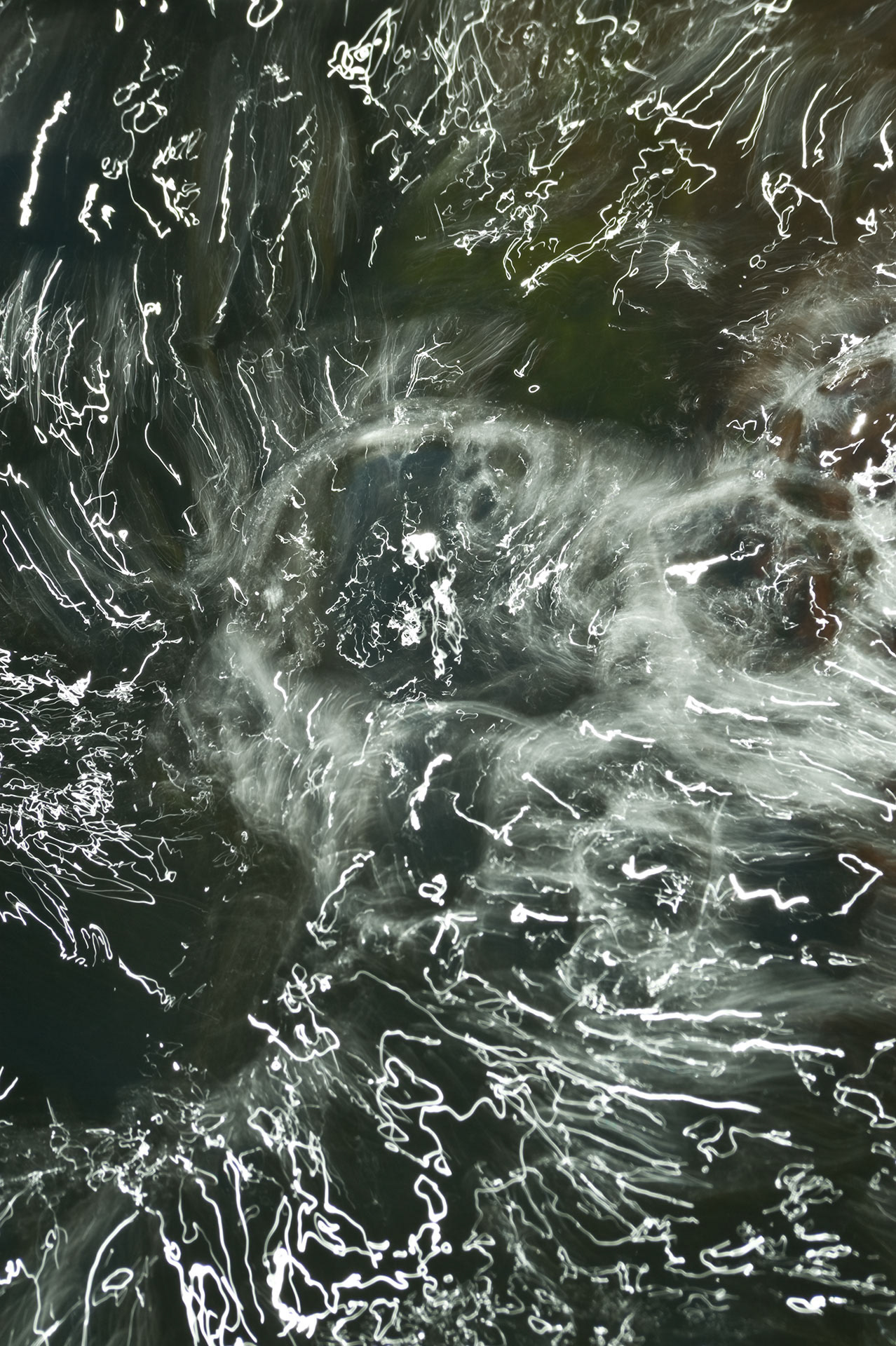

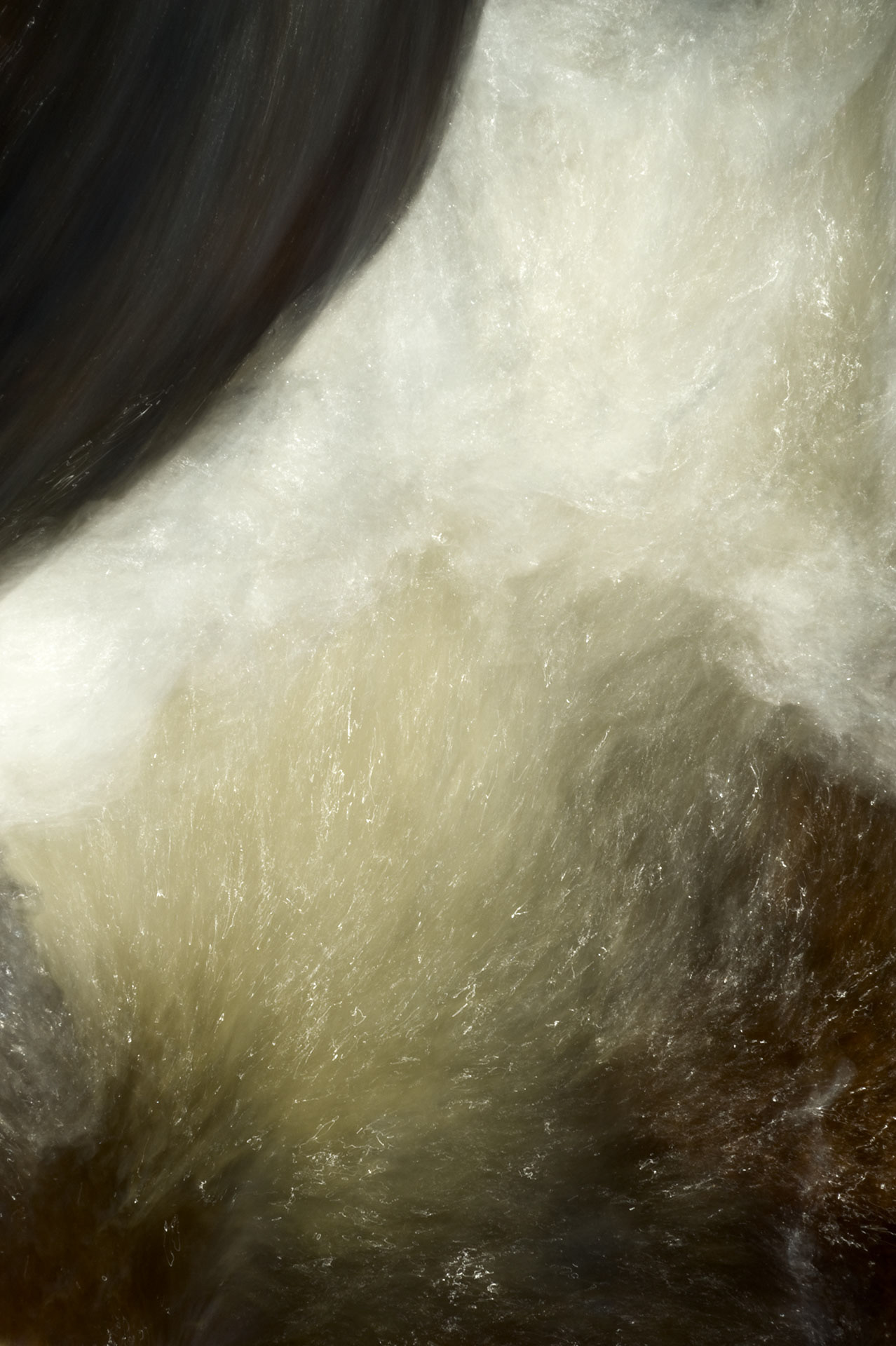

When First I Knew This Place is a series of photographs taken of the waters of the River Lett, at a place called Hyde Park, in the Hartley Valley, between Lithgow and the Blue Mountains. These photos also tell a story: of a woman’s grief and her healing.

The River Lett flows from a series of creeks that start on the sandstone ridge tops at Dargan, Bell and Mt Victoria, and fall, eventually, into the Cox’s River – a river named for the man who built the first road west, over the Blue Mountains. The sheer sandstone cliffs that surround the valley are so dominant it is a surprise to find that the base of the plains is smooth pink granite.

As a river named by Europeans the area carries many misnomers. The names the Wiradjuri and Gundungurra Aboriginal people used in this place are lost to us. The term River Lett is an adulteration of Rivulet. Hyde Park was gazetted as a reserve in 1881, and has been known as Hyde Park since at least 1897, but nobody remembers quite why. It is a place constantly renamed, remade, reshaped.

Today Hyde Park is a popular swimming hole for people from Lithgow and surrounding areas, who come for the deep cold water. The visits of locals mark the landscape with the traffic of cars and feet. It is a haven of snow gum, candlebark, ribbon gum, yellow box, lemon scented tea tree, river bottlebrush, river lomatia, Lissanthe strigosa and Bursaria spinosa – the blackthorn the endangered copper wing butterfly needs to breed. The precious Grevillea rosmarinifolia and Asterolasia buxifolia were thought to be extinct but grow well here. The water polishes the rocks glassy smooth, turning them into slippery dips and ice rinks for joyful kids.

But water is compelling for reasons beyond recreation. In Landscape and Memory, Simon Schama wrote about the perception of water and its cycles in the sense of bodily circulation and how big rivers like the Nile became places of sacrifice, propitiation, death and resurrection, fertility and libation. When the water is low, there is lamentation, with the floods come the myths of death and rebirth. Eastern people see rivers as loops; Western rivers are linear. Schama writes about Colonna’s battle to emerge from a forest, using the river to get his bearings.[1] Rivers help us orient ourselves. We all know to follow a river downstream.

Aboriginal people see rivers as the seat of women’s responsibilities: for love, water cycles, nurturing and local groups hold Hyde Park dearly, as a sacred women’s place. Wiradjuri woman Sharon Riley says Hyde Park is the head of the east-west flow, and a site for women to tell stories. A Bidigal woman of the Dharawal people, Frances Bodkin, who lives within huge looping Hawkesbury- Nepean River catchment, of which the Lett forms part, says “the rivers are the veins of the earth . . . the water is the blood of the earth . . . some would call them tears of the earth”.[2]

Hyde Park is where Julie came to remake herself, without knowing the healing powers of this place. The catalyst was loss. In 2004, in the peak of the drought, Julie’s partner died suddenly and tragically and grief became all and everything for her. But three years later the drought began to break and water flowed again in the Hartley Valley. Julie’s eyes, and her camera, were drawn to the water. When there were few people around, in the cold shifting seasons of spring and autumn, as the water ebbed and flowed, through granite that is the colour of grief: the same pink as ashes of roses and shiny, like headstones.

Making these photographs was a form of meditation for Julie. The process required close focus on the rushing soothing water. A focus no wider than the span of a hand. These were long exposures, 1/6 to 1/13 seconds, just enough time for the water to move through the frame, a little longer than the eye can hold focus. For Julie, this absorption meant she could forget about anything beyond the next photo.

Yet that tight focus did not limit her vision. She was always seeking the next photo although it was impossible to see what had happened at the time each shutter closed. When she got home, she would dump the day’s shots onto her computer, in their thousands. She would print the ones she wanted to look more deeply into. Water polishing pink, brown, quartzite, jade and chartreuse green from the rocks. Water becoming squiggles of neon light, sheets of limestone stalagmites, ice, mist. Just as the Golden Mean opens into the fullness of form, as fractals do, each photo uncurled and opened.

As children we suspend disbelief and spot shapes in clouds. If we do the same with these photographs they morph into full landscapes, with caverns, ridge tops, waterfalls, valleys, clouds, oceans. Some are painterly and evoke the elemental battle shown in Caspar David Friedrich’s The Wanderer in a Sea of Fog, others the light in Jules Bastien LePage’s Snow Effect Damvillers. Julie’s photos contain shipwrecks, archers, sextants, the colours of planetary rings, the vastness we can now explore through the Hubble Telescope.

Julie Williams’ series has been an exploration of what we may yet find – of the ways the smallness and stillness of grief – opens into vastness, the sublime, and new life.

[1] Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory, London: Harper Collins, 1995.

[2] Our Rivers, more than just water, Hawkesbury-Nepean Catchment Management Authority, 2010

[2] Our Rivers, more than just water, Hawkesbury-Nepean Catchment Management Authority, 2010

© 2011 Dr Naomi Parry

Dr Naomi Parry is a historian and was recently the Cultural Development Officer at Lithgow City Council, where she learned about Hyde Park for the first time.